Dashiell Hammett is considered one of the originators of the Hard-Boiled Detective Genre. While not the first to ever publish a hard-boiled story, he certainly came to define it. Raymond Chandler is perhaps the only other challenger for “most influential” on the genre itself, and Chandler credits Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels, and not Hammett, as his primary influence. Regardless, I have been on a bit of a hard-boiled kick as of late, with Parker last month, and now two Hammett novels in a row. It’s shaping up to be a crimey sort of year.

The Maltese Falcon

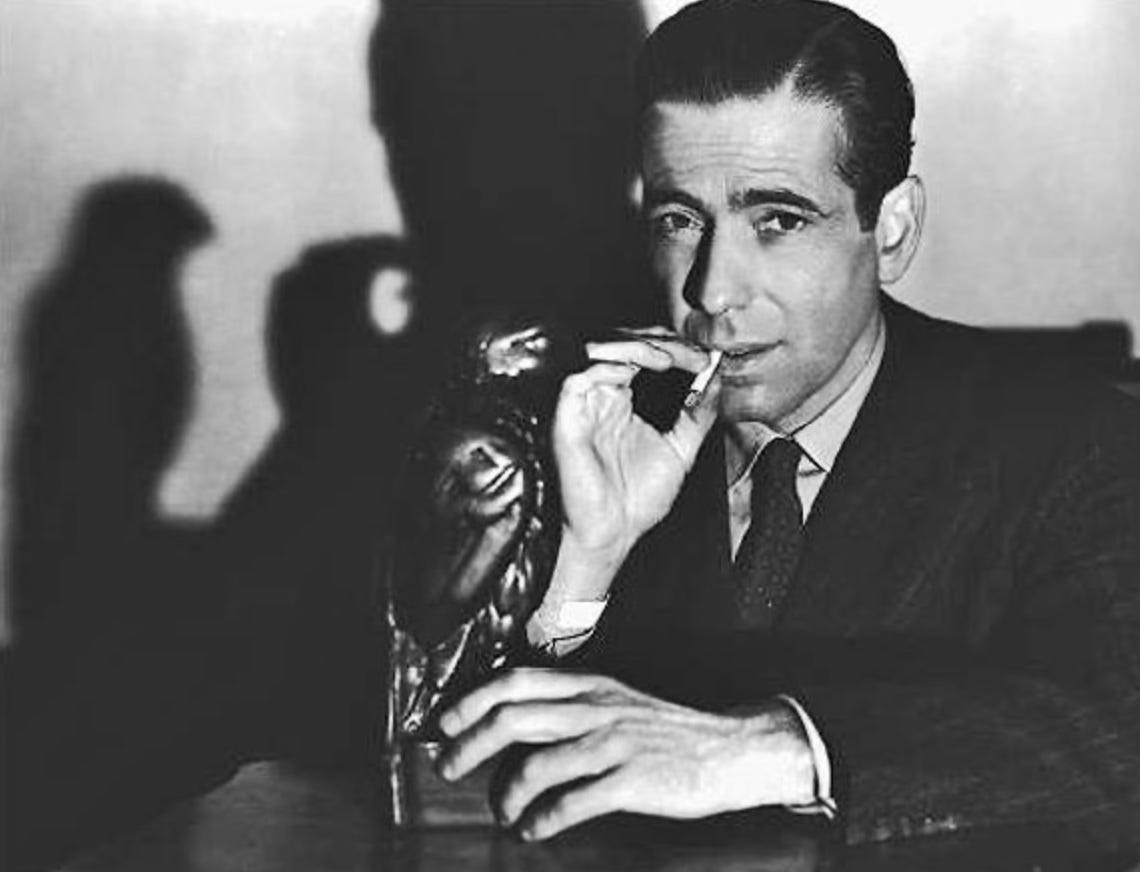

First off, The Maltese Falcon is one of those novels that is perhaps overshadowed by its movie adaptation. Sam Spade as played by Humphrey Bogart became the definitive archetype for the hard-boiled detective.

But what was truly impressive, at least to me, was how movie-like the novel itself read. And not only that, but how well that sort of narrative choice worked. There is a lot of talk in writer circles about the movie-if-ication of literature. And I think that discussion often has legs, and I largely agree with it. But, simultaneously, when done well, expertly even, it makes for some quite fun reading.

When he opened his apartment-door Brigid O’Shaughnessy was standing at the bend in the passageway, holding Cairo’s pistol straight down at her side.

“He’s still there,” Spade said.

She bit the inside of her lip and turned slowly, going back into the living room. Spade followed her in, put his hat and overcoat on a chair, said, “So we’ll have time to talk,” and went into the kitchen.

He had put the coffee-pot on the stove when she came to the door, and was slicing a slender loaf of French bread. She stood in the doorway and watched him with preoccupied eyes. The fingers of her left hand idly caressed the body and barrel of the pistol her right hand still held.

“The table-cloth’s in there,” he said, pointing the bread-knife at a cupboard that was one breakfast-nook partition.

She set the table while he spread liverwurst on, or put cold corned beef between, the small ovals of bread he had sliced. Then he poured the coffee, added brandy to it from a squat bottle, and they sat at the table. They sat side by side on one of the benches. She put the pistol down on the end of the bench nearer her.

“You can start now, between bites,” he said.

She made a face at him, complained, “You’re the most insistent person,” and bit a sandwich.

“Yes, and wild and unpredictable. What’s this bird, this falcon, that every-body’s all steamed up about?”

She chewed the beef and bread in her mouth, swallowed it, looked attentively at the small crescent its removal had made in the sandwiches rim, and asked: “Suppose I wouldn’t tell you? Suppose I wouldn’t tell you anything at all about it? What would you do?”

- From The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett

I include the excerpt above, because it’s beautiful. At least it is to me. And the whole novel is written like this. It paints a perfect motion-picture in your mind’s eye, with just in time details that make for a quite seamless sort of experience. This much detail would be tedious in the hands of a less skilled writer.

It’s also an incredible example of third person objective. Because the reader is never allowed access to Sam Spade’s mind, we are left to grapple with this man’s character solely through his actions. And through much of the story, we can’t be quite sure whether Sam Spade is a hero, a villain, or an anti-hero. He is a cunning and skillful operator, and as such never fully reveals his hand or his integrity until the very end, when everyone is right where he wants them. And that includes you, the reader.

“…Now on the other side we’ve got what? All we’ve got is the fact that maybe you love me and maybe I love you.”

“You know,” she whispered. “Whether you do or not.”

“I don’t. It’s easy enough to be nuts about you.” He looked hungrily from her hair to her feet and up to her eyes again. “But I don’t know what that amounts to. Does anybody ever? But suppose I do? What of it? Maybe next month I won’t. I’ve been through it before—when it lasted that long. Then what? Then I’ll think I played the sap. And if I did it and got sent over then I’d be sure I was the sap. Well, if I send you over I’ll be sorry as hell—I’ll have some rotten nights—but that’ll pass…”

- From The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett

Red Harvest

Red Harvest in a lot of ways may have come first for this specific story type, but it certainly did not do it the best. It’s a story/plot that has been dozens of times, inspiring both Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and the Clint Eastwood spaghetti western A Fistful of Dollars.

The steadfast and sturdy Continental Op has been summoned to the town of Personville—known as Poisonville—a dusty mining community splintered by competing factions of gangsters and petty criminals. The Op has been hired by Donald Willsson, publisher of the local newspaper, who gave little indication about the reason for the visit. No sooner does the Op arrive, than the body count begins to climb . . . starting with his client. With this last honest citizen of Poisonville murdered, the Op decides to stay on and force a reckoning—even if that means taking on an entire town.

- Red Harvest, back cover copy

I enjoyed this novel a lot less than the Maltese Falcon and much of that had to do with the narrative style. Where the Maltese Falcon is written in a clear and crisp third person, Red Harvest is written in a choppier more stream of conscious first person. Additionally, it quickly became hard to follow, at least for me. So many competing factions and people and names are hurled at you that it becomes impossible to track what is going on. And in this way, it’s less of a detective novel and more of an action novel. Perhaps, even a western. When seemingly everyone in the entire town is a dirt bag or is somehow crime-involved it’s hard to really care who murdered who other than for the sake of pedantry.

Which is another reason it didn’t quite connect with me. I just didn’t really care at a certain point. The Continental Op (truly the original man with no name) is a fine enough protagonist, but it’s fairly hard to care about his mission when there’s no one in the town really worth saving. Or at least none that we care for. The whole thing is an exercise in cynicism. Even Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars took some time out to make us care about the average townsperson via the enstranged mother and her small child.

I spent most of my week in Ogden trying to fix up my reports so they would not read as if I had broken as many agency rules, state laws and human bones as I had.

From Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett

However, it’s not bad. The few times when I found my footing in a scene, there was some good stuff. Both the opium dream and the reveal of a murdered femme fatale being quite memorable and a remarkably good turning point in any story. There is an energy to the novel that compels you forward, even though it’s mostly a dark energy. For a much better and thoughtful review I recommend Red Horizon’s write up in Copper & Blood: Dashiell Hammett’s Montana Mayhem. Ultimately, I just wish I could’ve enjoyed it as much as I thought I was going to ahead of time.

These are both terrific. The classic crime novels are hard to beat. I really loved the Sam Spade character. He's not a heel and he's not a boy scout. Like you point out, you're not sure what he's going to do next. And I love writing in that style. Switching POV is so powerful when you're doing third-person limited. I love it when we get the protagonist's point of view and then it switches to the villain and you can't be sure what the protagonist is doing or thinking. Fresh perspectives keep the narrative fresh throughout. Great post, Frank.

That first passage flows well because he uses actions and dialogue to mask the descriptive elements of the scene. Cool.