I just finished A Bullet For Cinderella (originally titled On the Make before being changed back for the second edition) by John D. Macdonald and what a ride. Macdonald is most widely known for his Travis McGee series, a hardboiled character that lives on a houseboat and works as a “salvage expert.” A Bullet For Cinderella is not a McGee novel, nor is it even hardboiled, rather, it is a standalone noir.

Noir and Hardboiled are often treated as interchangeable genres, and some of that is due to the aesthetic definition noir has with regard to film (different than its conventions as a literary genre). If you’re interested in more of a deep dive Vigilante Crime did an excellent little essay on the differences.

Regardless, A Bullet For Cinderella is a textbook noir. An everyman in over his head, dead private eyes, dames and femme fatales, a pile of stolen cash.

Tal Howard, a Korean War vet and former POW, blows into the small town of Hillston (state never named) about a year after getting back from the war. Tal has just left his long time fiancé who he got engaged to before the war. According to him, they drifted apart, or rather, he had come back changed. A big theme of the novel revolves around this change. More on that later, as that is mostly what I want to talk about.

In the POW camps, Tal was friends with a man named Timmy Warden who died before they could be rescued. Timmy had revealed to Tal that he stole about 60k from his brother George’s company (he was also sleeping with said brother’s wife). Timmy buried the money before he left and it was still there for the taking. Before he dies, Timmy tells Tal that a girl named Cindy will know the spot where he hid the money if he ever wants to go get it.

And so, armed with this single clue, a disillusioned Tal travels to Hillston to find the stolen money and hopefully some type of a new life. In Hillston, Tal looks up Ruth, an old flame of Timmy’s, to see if she has any info as to the identity of this “Cindy.” I should mention here that Tal has carried a picture of Ruth this whole time. He took it off Timmy when he died. To Timmy, Ruth was the girl that got away, and unknown to Tal, she will serve a similar function for him.

Tal also finds out that a man named Fitzmartin has been working for George Warden for the last year. Fitzmartin was a fellow POW in the camps, one that all the other men hated and had vowed to kill. Fitzmartin is very clearly a might makes right type of psychopath. He is strong, mean, and violent. The other POWs hated him because he refused to cooperate with them for the survival of the group and openly despised them for being weak. He was a bully, but he ate well. Fitzmartin, having overheard Timmy’s story about the money, has come to Hillston in order to look for it, but without any leads, he has made very little progress. He also doesn’t know about the girl named Cindy.

George Warden, Timmy’s poor brother, is doing especially bad. His wife ran off with a salesman shortly after Timmy left, and he is also apparently selling off parts of his businesses to fund his newfound alcoholism.

Expect heavy spoilers from here on out.

Tal spends most of the first half of the book looking for Cindy. Around the midpoint he finally finds her. Cindy was a pet name that only Timmy called her, which was itself short for Cinderella, a part she played in the school play. Her real name is Toni Rassell. She is something of a femme fatale and runs in bad circles. She’s been picked up by the police a few times for running a variation of the “badger game” which is a type of con. Tal finds out that she does indeed know where the money is buried. Its in a cave where her and Timmy used to hook up. Tal and Toni agree to go find the money, split it, and run off together for as long as the money will last.

While Tal has been tracking down Cindy, Fitzmartin has been following Tal. Fitzmartin next kidnaps Ruth and brokers a deal with Tal. The money for Ruth. Of course Tal can’t tell Toni because he needs her to show him where the money is buried. The rest of the story barrels towards its conclusion from here.

I’ll stop to avoid totally spoiling how things play out, but I do want to discuss some of the themes at play.

Animal vs. Man

One of the reasons John D. Macdonald has such an enduring legacy and rabid readership is because he had such a keen eye for human nature. That sort of talent is put to good use here. All of the characters are well fleshed out and quite driven by their own demons. But what really kept me thinking about this book long after I put it down was how Macdonald demonstrated his themes.

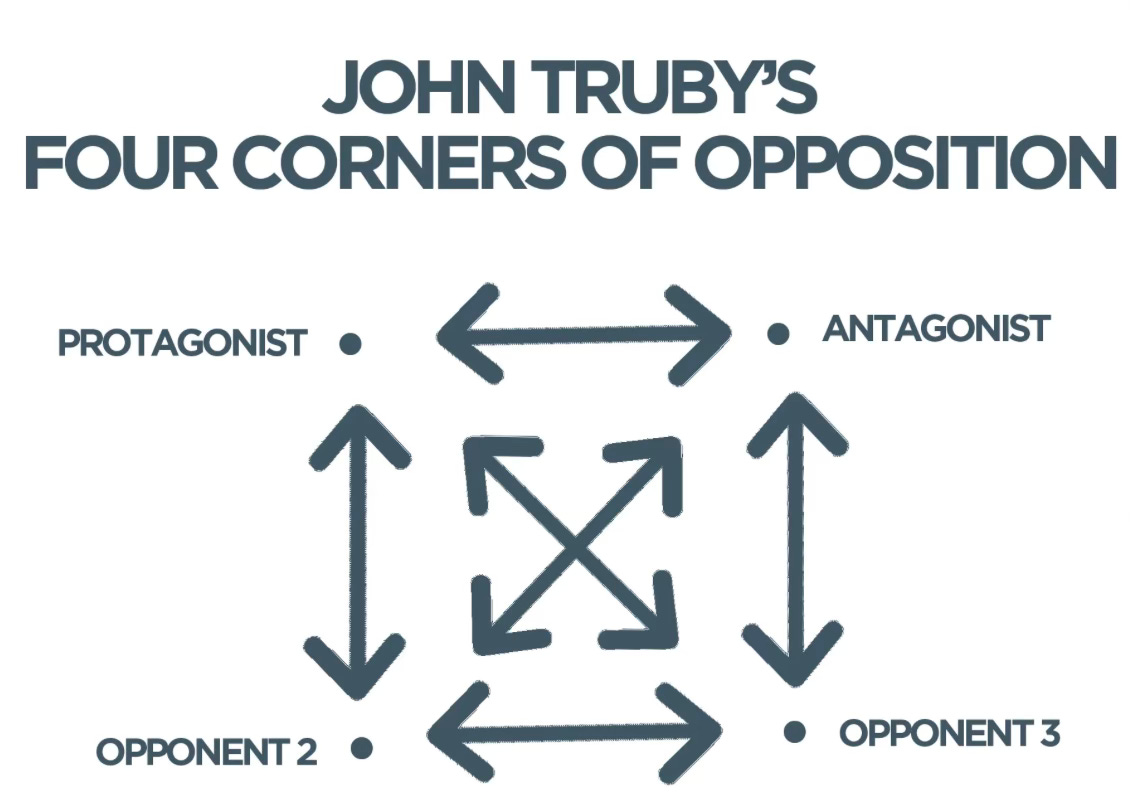

If you are a writer you may be familiar with John Truby’s Four Corner Opposition Framework.

In average or simple stories, the hero comes into conflict with only one opponent. This standard opposition has the virtue of clarity, but it doesn’t let you develop a deep or powerful sequence of conflicts, and it doesn’t allow the audience to see a hero acting within a larger society…

There are a thousand different ways to diagram characters and the moral polarities they represent, the point is, that by creating thematic conflict between four characters instead of just two, you create a more complex understanding of a theme and/or moral premise.

This is a neat little video if you’re a craft nerd, but I digress.

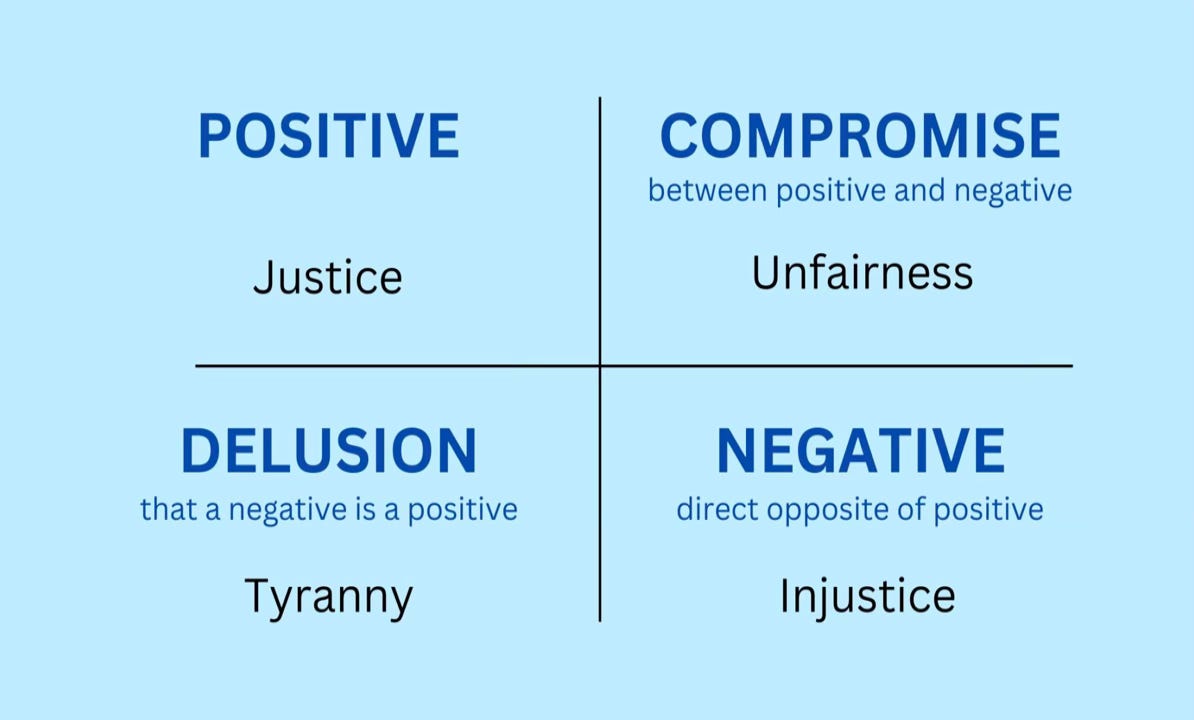

In A Bullet for Cinderella, we find a Tal that is harder than when he left for the war. Being a POW has changed him. It has hardened him in some ways, and softened him in others. The thematic question revolves around survival and civilization. Are the traits that are good for survival good for society, and if one becomes too good at survival in the most strict, Darwinian sense of the word, can they ever find peace within society?

Fitzmartin represents pure survival. He is a violent psychopath that despises cooperation as a sign of weakness.

Ruth represents pure civilization. She is the face of high trust society.

Tal is caught somewhere between Fitzmartin and Ruth.

Toni is almost a perfect mirror of Tal. Like him, she is a streetwise survivor. But she’s not particularly depraved. She’s loose, but not a whore, she has standards and has a heart.

The following exchange between Ruth and Tal is very demonstrative of the major changes the POW camp has wrought on Tal’s character. Also it’s just especially great Macdonald dialogue.

I felt ill at ease with her. I had never come across this particular brand of honesty. She had freely given me an uncomfortable truth about herself, and I felt bound to reciprocate.

I said, too quickly, “I know what you mean. I know what it is to feel guilty from the man’s point of view. When they tapped my shoulder I had thirty days grace before I had to report. I had a girl Charlotte. And a pretty good job. We wondered if we ought to get married before I left. We didn’t. But I took advantage of all the corny melodrama. Man going to the wars and so on. I twisted it so she believed it was actually her duty to take full care of the departing warrior. It was a pretty frantic thirty days. So off I went. Smug about the whole thing. What soft words hadn’t been able to accomplish, the North Koreans had done. She’s a good kid.”

“But you’re back and you’re not married?”

“No. I came back in pretty bad shape. My digestive system isn’t back to par yet. I spent quite a while in an army hospital. I got out and went back to my job. I couldn’t enjoy it. I used to enjoy it. I couldn’t do well at it. And Charlotte seemed like a stranger. At least I had enough integrity not to go back to bed with her. She was willing, in the hopes it would cure the mopes. I was listless and restless. I couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me. Finally they got tired of the way I was goofing off and fired me. So I left. I started this—project. I feel guilty as hell about Charlotte. She was loyal all the time I was gone. She thought marriage would be automatic when I got back. She doesn’t understand all this. And neither do I. I only know that I feel guilty and I still feel restless.”

“What is she like, Tal?”

“Charlotte? She’s dark-haired. Quite pretty. Very nice eyes. She’s a tiny girl, just over five feet and maybe a hundred pounds sopping wet. She’d make a good wife. She’s quick and clean and capable. She has pretty good taste, and her daddy has yea bucks stashed.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t feel guilty.”

I frowned at her. “What do you mean, Ruth?”

“You said she seems like a stranger. Maybe she is a stranger, Tal. Maybe the you who went away would be a stranger to you, too. You said Timmy changed. You could have changed, too. You could have grown up in ways you don’t realize. Maybe the Charlotte who was ample for that other Tal Howard just isn’t enough of a challenge to this one,”

“So I break her heart.”

“Maybe better to break her heart this way than marry her and break it slowly and more thoroughly. I can explain better by talking about Timmy and me.”

“I don’t understand.”

“When Timmy lost interest the blow was less than I thought it would be. I didn’t know why. Now after all this time I know why. Timmy was a less complicated person than I am. His interests were narrower. He lived more on a physical level than I do. Things stir me. I’m more imaginative than he was. Just as you are more imaginative than he was. Suppose I’d married him. It would have been fine for a time. But inevitably I would have begun to feel stifled. Now don’t get the idea that I’m sort of a female long-hair. But I do like books and I do like good talk and I do like all manner of things. And Timmy, with his beer and bowling and sports page attitude, wouldn’t have been able to share. So I would have begun to feel like sticking pins in him. Do you understand?”

“Maybe not I’m the beer, bowling, and sports page type myself.”

She watched me gravely. “Are you, Tal?”

It was an uncomfortable question. I remembered the first few weeks back with Charlotte when I tried to fit back into the pattern of the life I had known before. Our friends had seemed vapid, and their conversation had bored me. Charlotte, with her endless yak about building lots, and what color draperies, and television epics, and aren’t these darling shoes for only four ninety-five, and what color do you like me best in, and yellow kitchens always look so cheerful—Charlotte had bored me, too.

My Charlotte, curled like a kitten against me in the drive-in movie, wide-eyed and entranced at the monster images on the screen who traded platitudes, had bored me.

I began to sense where it had started. It had started in the camp. Boredom was the enemy. And all my traditional defenses against boredom had withered too rapidly. The improvised game of checkers was but another form of boredom. I was used to being with a certain type of man.

He had amused and entertained me and I him. But in the camp he became empty. He with his talk of sexual exploits, boyhood victories, and Gargantuan drunks, he had made me weary just to listen.

The flight from boredom had stretched my mind. I spent more and more time in the company of the off-beat characters, the ones who before capture would have made me feel queer and uncomfortable, the ones I would have made fun of behind their backs. There was a frail headquarters type with a mind stuffed full of things I had never heard of. They seemed like nonsense at first and soon became magical. There was a corporal, muscled like a Tarzan, who argued with a mighty ferocity with a young, intense, mustachioed Marine private about the philosophy and ethics of art, while I sat and listened and felt unknown doors open in my mind.

Ruth’s quiet question gave me the first valid clue to my own discontent. Could I shrink myself back to my previous dimensions, I could once again fit into the world of job and Charlotte and blue draperies and a yellow kitchen and the Saturday night mixed poker game with our crowd.

If I could not shrink myself, I would never fit there again. And I did not wish to shrink. I wished to stay what I had become, because many odd things had become meaningful to me.

“Are you, Tal?” she asked again.

“Maybe not as much as I thought I was.”

“You’re hunting for something,” she said. The strange truth of that statement jolted me. “You’re trying to do a book. That’s just an indication of restlessness. You’re hunting for what you should be, or for what you really are.” She grinned suddenly, a wide grin and I saw that one white tooth was entrancingly crooked. “Dad says I try to be a world mother. Pay no attention to me. I’m always diagnosing and prescribing and meddling.” She looked at her watch. “Wow! He’ll be stomping and thundering. I’ve got to go right now.”

MacDonald, John D.. A Bullet for Cinderella (Murder Room) (Function). Kindle Edition.

In one way, we see the camp has made Tal something closer to Ruth. Someone for who “beer and bowling and sports page attitude” no longer describes, someone interested in art and philosophy and books. But simultaneously, he’s also become more like Fitzmartin. He’s hunting for the same stolen money. Both for the thrill of it, as well as the reward of it… money that a civilized man would give back to George.

Ultimately, Ruth represents a path for him to reintegrate back into society, while Toni represents a path towards the survivalist, the human animal.

I’ll avoid totally spoiling how these potentials and themes end up playing out, but you should pick up a copy (its free on Project Gutenberg).

I give it Five Dead Dicks out of Five.

MacDonald has very similar arguments in his various Travis McGee novels as well. It is clear the war, serving in Burma with the OSS, changed MacDonald on a fundamental level. He wasn't going to be happy living either the corporate or bureaucratic government post-war life like many military officers of his generation.

The was my first John D. book, so I'll always think of it fondly.